This is a transcript from our podcast episode with Frank Ostaseski about meditation and death.

Axel Wennhall

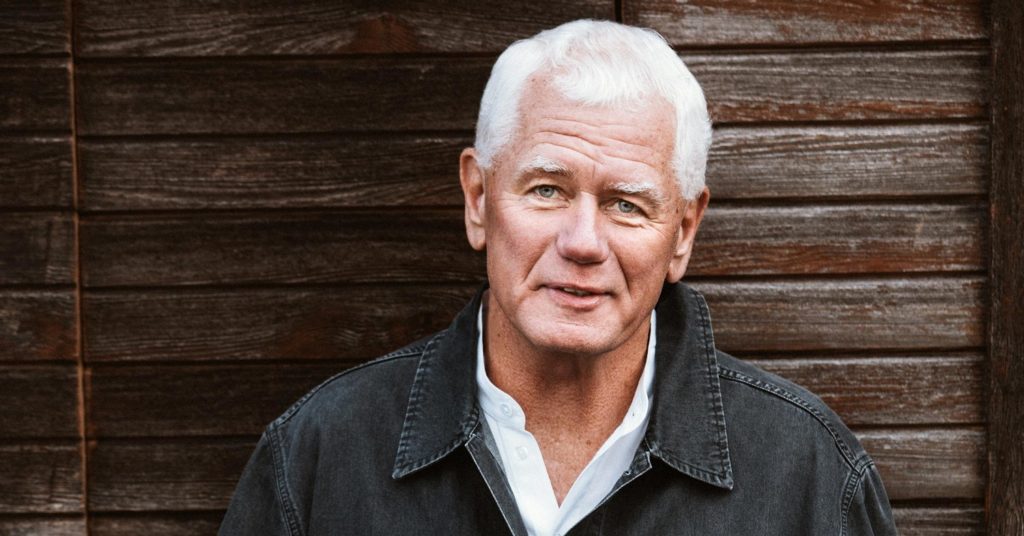

Hi and warm welcome to the Swedish podcast Meditera Mera, which in direct translation means meditate more. With me, Axel Wennhall, who asks the questions, and producer Gustav Nord. This is our third episode in English, and we’re currently sitting here in Stockholm, and we are waiting to call and speak to Frank Ostaseski, who’s enjoying his morning on the West Coast in the States. While we started to record our interview with Frank, he had a power outage back home. So in the middle of our landing meditation that he generously offered to guide, we lost him. But luckily for us, and luckily for you, the power came back on. So let us present Frank. Frank Ostaseski lives in Sausalito. He’s a Buddhist teacher and a pioneer in the end-of-life care. In 1987, he co-founded the Zen Hospice Project, the first Buddhist hospice in America. And in 2004, he created the Metta Institute. He has lectured at Harvard Medical School, the Mayo Clinic, and Wisdom 2.0, and he teaches at major spiritual centers around the globe. Frank is also the 2018 recipient of the prestigious Humanities Award from the American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine. His groundbreaking work has been highlighted on the Oprah Winfrey Show and honored by the Dalai Lama. And he’s the author of The Five Invitations, Discovering What Death Can Teach Us About Living Fully. And meditation and death are exactly what we will discuss with Frank. What can death teach us about living? How is death and meditation interrelated? And what advice do Frank have for all of us who want to meditate more? There we go.

Okänd

There, sorry my microphone is in trouble.

Frank Ostaseski

Hi, can you hear me okay?

Axel Wennhall

Yes, yeah. Do you hear us?

Okänd

One, two, one, two, one, two. Listen.

Axel Wennhall

Hi Frank, it’s great to connect.

Frank Ostaseski

Very happy to be with you.

Axel Wennhall

So, this might sound strange for some, but this is actually a small dream coming true for us. And that might seem weird and perhaps even morbid that it is a dream to speak about meditation and death. But I came across your book, I think I first found out about it when you were a guest in Sam Harris podcast, Making Sense, I think it was called Waking Up back then. And I read some wonderful books since I started my spiritual journey a few years ago. But this is definitely on the top of that list. It’s very deep and so many great insights how to live more fully. And I’m very eager and very grateful for getting that opportunity to discover those insights with you today.

Frank Ostaseski

Well, I’m very delighted to be with you and your listeners of course. And I think it’s a dream if we pretend that death doesn’t happen to us. This is the greatest dream. This is the greatest illusion that we often fall prey to. So I’m glad that we’ll have an honest and frank discussion about how the contemplation on death and meditation can help us to live a much more whole, full, rich life.

Axel Wennhall

And this is also an interactive podcast.

Frank Ostaseski

So we have the eyes, the ears, the taste, the smell, sense of touch. These are the doors of perception. And so this is how we know our life and interact with the world. Let’s open all those doors and windows. And let’s begin by bringing our attention very precisely and carefully to the experience of hearing. You might be aware of the sounds in the room in which you’re sitting, sounds outside the building, the sound of my voice. But if you can, see if you can notice the silence as well. Notice if the silence has any boundaries. And just for a moment, recognize the stillness of the silence. And how sound emerges from the silence and returns to it. And yet the silence itself is undisturbed. This can speak to something very fundamental about our most essential nature. So as we enter into this discussion, let’s do our best to try and continue to sense our bodies, to keep our sense doors open, and to be cognizant of the silence, the background, if you will, for all things. And I think if we do this, we’ll have a much greater benefit from this podcast than just listening to my words. Listen to yourself as you listen to our conversation. Thank you very much.

Axel Wennhall

This is the best part of this job, getting the opportunity to do those meditations. So first of all, I’m curious, where were you at in your life when you started to meditate or found meditation?

Frank Ostaseski

I was relatively young. I was in my late teens. I tried everything else sex, drugs, and rock and roll, you know, to try and escape the challenges of my life. And none of them really worked, except quite temporarily. And when I found meditation, it made sense to me. It just felt right. I didn’t have to believe anything. I didn’t have to take on a belief system. I could just trust my own direct experience. And so since that time, now 40 more, more than 40 years, I’ve been engaged in that practice of exploring the mind, heart, and body through the practice of meditation.

Axel Wennhall

How come you started the Zen Hospice? So how was sort of your spiritual practice and how led you there?

Frank Ostaseski

Well, the Zen Hospice, which was begun in San Francisco as a project of the San Francisco Zen Center, we started it with not a very big plan in mind, actually, actually. We thought there was a natural match between people who were cultivating what we might call the listening mind or the listening heart through meditation practice, and people who really needed to be heard at least once in their life, people who were dying. And so we chose to focus on people who were living with little or no support. Mostly the people we worked with were homeless. They lived on the streets of San Francisco. So I changed a lot of diapers on park benches behind City Hall. And you see, we just thought these two groups of people had something to offer each other. It wasn’t that we were the good guys trying to come and help the poor homeless folks. It was that we believed, those of us who are practicing meditation believed, there was something we could learn also from these individuals. And so it was a kind of act of mutual benefit, really. Yeah. When you sit close to the precipice of death, right on the edge, you learn something. You learn things that the culture needs. That we need to live fully. And so whenever I was with someone who was coming close to the end of their life, I did my very best to thank them for all they were offering me. You know, we have wonderful galleries in every major city where great paintings hang. We also have beautiful places in which people come to die. And maybe we should go to those people and say to them, you know, please be my teacher. Show me what’s really important so that I can live my life with some degree of integrity. So that’s how we started. And we just made it up as we went along. We didn’t really know. We had a small house and first we just moved in one patient and we took care of them and the next thing you know we could take care of six and then we started a palliative care service in the county’s hospital. And over the course of the time I was there we took care of thousands of people who died and we trained thousands of volunteers to sit with them. And it was this kind of fusion of spiritual insight and very practical social action.

Axel Wennhall

When was this? When did you start?

Frank Ostaseski

We started in mid 80s 1987 actually is when we started and I stayed there for about 20 years and then moved on to allow other people to guide it and I created another organization called the Meta Institute which was an educational organization to teach what dying folks had showed us. And really to emphasize the importance of mindful and compassionate care but also to translate the lessons from dying that have a relevance for all of us in living a wholesome life.

Axel Wennhall

And some of what you learned and what you are now explaining for us is the five invitations that you have in your book. But before we are we’re gonna explore them I would just like to ask you about there’s one thing in the book that I made a note on and sort of that made a lot of sense to me but I haven’t really thought about it before I read it in your book and that was you’re sort of describing to be of service or helping or fixing. Could you please elaborate a bit on those three differences?

Frank Ostaseski

Sure well you know often when we help you know like when you help your friend move his house right and you help him move his table and his bed and these things you create oftentimes a relationship of debt actually. If you helped him now he has to help you. Yeah that’s the first thing about helping but also helping tends to occur from a vantage point of strength. We are the strong one and we help the weak one. And so this is an imbalanced relationship. Yeah the same is true of fixing. You know when there’s a problem we we like to apply solutions of course and that’s appropriate sometimes. And it’s good to fix cars but not people. We should recognize that people are whole human beings and they can contribute a great deal to their own healing. When we help people we see them as weak. When we fix people we see them as broken. But when we serve people we see them as whole naturally whole. And we recognize in that act of service there is another kind of thing going on. There is one there’s a balance of relationship but two we feel ourselves serving something larger than just the two of us. We feel we’re participating something larger than both of us like something that includes both of us but is not limited to both of us. Something like that. So we could say that helping, fixing and serving are ways to approach life. You know when we help we see life as weak. When we fix we see life as broken. When we serve we see life as whole. So the Zen hospice was founded in that spirit of physically whole. Then they start responding that way. You know like for example we had a man who was quite paranoid and psychotic and I found him in this in the city park the Golden Gate Park in the middle of San Francisco under some bushes. And I invited him to come and stay with us. It turned out he had terminal lung cancer. His psychiatrist came to see us after about three or four months in our care and he said what did you do to him? What medication did you give him? And I said love. We gave him a lot of love and we didn’t treat him like he was crazy. And you know he began to behave differently. Now I don’t want to suggest it was any kind of miracle or that this is the solution for mental illness but it certainly isn’t an aid. When we can see and respond and hold a mirror to someone’s intrinsic wholeness. Yeah I think that helps.

Axel Wennhall

So let’s dig into those five invitations that you bring up in your book and the first one is don’t wait. What do you mean with don’t wait and what have you learned?

Frank Ostaseski

Well first I want to say that these invitations are really guidelines that we used at Zen hospice as a kind of way to show us how to interact with patients and all of them came from the patients. I didn’t invent these. They’re my synthesis of what I learned from the patients. So I really want to give them full credit because they’re my teachers and I always feel like when your teachers are in the room with you you behave very honestly. Yeah so I like to honor them by acknowledging them. So the first one as you say is don’t wait. The waiting is full of expectation. Waiting for the next moment to arrive we miss this one. I can’t tell you how many times I’ve been with a family whose mother is dying and they’re asking me when is she going to die? When is she going to die? And waiting for the moment of death we miss all the moments in between. So don’t wait. This is a kind of encouragement to live in the immediacy of our life. Do not postpone our life for some other time. It doesn’t mean that we should run about helter-skelter, you know, trying to get, you know, all the toys we can possibly get. It means to settle back a little bit, to not be in such a hurry, to not be swept away by our ideas about the future. So here’s an example, practical one. A friend of mine called me to say his mother was dying and he lived in San Francisco and his mother lived in Toronto, Canada. And so the doctor said that the mother had a few weeks to live and he said to me when should I go? And I said I don’t know, come and talk. And so he came to my house and we sat as you and I are sitting and I asked him some questions about his mother and he told me what the doctor said and then he began to explain his relationship with his mother. And as he did I could see his lower chin start to tremble and I could see the color change in his cheeks. And I said I think you should go tonight. And he was surprised. He had business the next day and he didn’t think he could go. And I said no, no, please go tonight. And so he did. He got on an airplane and he flew an overnight flight and he arrived in Toronto at 10 in the morning and at 1 in the afternoon he was sitting with his mother when she died. Don’t wait. I mean here’s the thing, Axel, you know, to imagine that at the time of our dying we are gonna have the mental clarity, the emotional stability, the physical strength to do the work of a lifetime is a ridiculous gamble. And so our work is to practice now. That’s the heart of meditation practice, right? Practice now. See what it can show us here and now. It’s not about preparing for some end moment, you know, the final moment of our life when the breath stops. It’s about living every moment, fully and completely. That’s don’t wait.

Axel Wennhall

Gustav and I, we had a discussion before we got the opportunity to speak to you and the discussion was what would you do if you had one year left to live? And another one of those, I think it was in Stephen Batchelor’s book Buddhism Without Beliefs, there is a meditation he explains and it just goes to ask yourself, since that alone is certain and the time of that uncertain, what should I do? And for me that just it sort of brings such a wakefulness into the moment. It’s sort of not that everything becomes so clear but it’s sort of yeah, it becomes definitely clearer what is important.

Frank Ostaseski

Yes, I agree. And I think when people ask me this question, I would like to be able to think that I would do nothing different than what I’m doing right now. That I wouldn’t save up something for the moment of my death and try and squeeze it in there in the last few weeks. I would like to think that my death was a culmination of my life, a full-throated living of my life.

Axel Wennhall

And that leads us into the second imitation, welcome everything, push away nothing.

Frank Ostaseski

Yes, people often have a hard time with this one.

Axel Wennhall

Yeah, it’s the same with the word acceptance.

Frank Ostaseski

Does it even make sense? Is it intelligent? Welcome everything? Push away nothing? I mean, it sounds a little crazy-making. But here, when I use the word welcome, you know, I think of welcome as a kind of invitation. You know, a kind of open, armed invitation. My wife is British, and they don’t use the term welcome in England, you know. And so she says, What do you mean by welcome? Then what I did was I outstretched my arms as far as I could, and I said, This is what it means to welcome. And I gave her a big hug. So the welcome doesn’t mean that we have to like what comes or that we have to agree with it, any of that sort of thing. It means that we’re willing to meet it. That’s all. We’re just willing to meet it. It’s on our front doorstep, but we’re willing to meet it. You know, the great African-American writer James Baldwin, he said, There are a lot of things in this world that we cannot change, but nothing can be changed until it’s met. And so I think it’s a beautiful encouragement to really step in, to see what something has to teach us. There’s a story I share in the book about an eminent psychiatrist who had dementia. And some mutual friends went to his house, rang his doorbell, and he opened the door, and he looked at them blankly, and he said, I’m so sorry, I can’t recognize faces anymore, and I don’t remember people’s names very well, but I do know that this is my home. And my home has always been a place where people are welcome. So if you’re standing on my doorstep, I know that my job is to invite you in. Please come in. Now, what kind of life do we have to lead that allows that sort of habit to grow and be expressed even in a confused mind? So I think this is what it means to welcome everything. In order to know something, we have to allow it in. We have to accept its presence. And then we can study it. And then we can find what are the skillful responses to meet the challenges of our lives. But if we keep it at arm’s length, we can’t know anything about it. And we are always victim to it in that way. So I think this is a way to have choice in our life, really have choice, to welcome everything, all of the beauty and horror of the world. Yeah, I mean, I’m practicing welcoming, trying to tell you, you know. But honestly, I don’t know. You know, I have lots of wonderful teachers who have said things to me about it, but honestly, I don’t know. But it seems to me that everything else in life is characterized by impermanence. You know, this day comes and goes. This conversation will come and go. You know, this morning’s breakfast, come and gone. Last night’s lovemaking, come and gone. But also each of these things leaves a kind of residual, we could say, a kind of flavor of it. When a tree falls in the woods, it becomes a log and that log rots and becomes other things, doesn’t it? So impermanence is not just about endings. It’s about the law of change and becoming. Everything becomes something else. We don’t know exactly what form it will take, but everything becomes something else. Now, why would we as human beings be any different than everything else in nature? Now, I don’t promise that we’re going to come back as, you know, the queen of Egypt or something, but I think this is a foolish idea that we have about such things as reincarnation. But we do know that our influences live in the lives of others. That’s another way that we become. So I don’t think death is a false start. I think it’s a way we scare ourselves by thinking of it that way.

Axel Wennhall

I heard you say in another interview that you had experienced that the way people were thinking about death and what happens thereafter can also shape their dying process.

Frank Ostaseski

Absolutely, in our living process for that matter. I mean, it’s a regular question that I ask people. What do you think is going to happen when you die? I don’t know and I’m not looking for the correct answer. I just think that whatever story they’re telling themself, whether it’s a religious story or a cultural one or a family story, it’s certainly affecting their psyche and the way in which they meet the experience of dying. We could be telling each other frightening stories or comforting stories, but we have to sort out our beliefs from what we actually know. A funny example is a man who was in our hospice who was the president of the California Atheist Association. And he came to us at Zen hospice to die. And I was very happy that he felt comfortable coming there. That he didn’t feel as though we would impose any dogma on him. And of course, like everyone else, I asked him the question, What do you think is going to happen when you die? And he thought for a minute and he said, Nothing. Nothing. And I said, What do you mean nothing? Like a dial tone on the phone? He said, No, no, no, not like that. I said, Well, will you smell things? He said, No, I won’t have a nose. I said, Will you hear things? He said, No, I won’t have ears. I said, Well, what’s this nothing like? And he said, Well, it’s like your molecules mixed with all the other molecules in the universe. And you feel yourself to be part of everything. And I thought, Well, that’s a pretty good nothing. He’s gonna be okay.

Axel Wennhall

That’s an amazing story.

Frank Ostaseski

And I don’t try to impose my ideas on other people. I explore with them. I inquire with them to discover what’s so for them. It’s not my place to shape someone else’s dying. It’s my place to accompany them. And to think of dying as a kind of ceremony that we’re going through together.

Axel Wennhall

And the third invitation, Bring your whole self to the experience. What do you mean by the whole self?

Frank Ostaseski

Yeah, well, we all like to look good, right? I mean, we spend a lot of time primping and preparing ourselves each morning. And we like to seem intelligent or that we have expertise, or at least that we’re not as much of a mess as we know we actually are, right? We like to put forward a good image to the culture. So to bring your whole self, it means to bring all of it. To bring the parts that you hide, the parts that embarrass you. It means also to bring your fear forward and your grief forward. You know, when I’m working with someone who’s dying, I’m experiencing my own grief, my own sense of loss, my own fear. And I think if I know those experiences intimately, they allow me to form an empathetic bridge to the person whom I’m speaking to. You know, when you’re afraid and someone comes in and says to you, I understand completely. You’ll know that they’re just guessing if they haven’t really explored fear, right? When you get afraid, can I ask you, Axel, when you get afraid, how do you know you’re afraid?

Axel Wennhall

Hmm, I feel contracted. I feel, especially in my body, chest area, stomach, right?

Frank Ostaseski

Beautiful. So you feel this contraction in the body. How about in your mind? What do you notice in your mind?

Axel Wennhall

Hmm, same thing. And also, yeah, contraction is the first word that comes up. Sure. And also, I feel that I am in my head when I’m afraid.

Frank Ostaseski

So all the energy rushes to your head in a way. And sometimes we feel frozen when we’re in fear. You know, we can’t think, we get confused, examples like that. But here’s the thing I want to point to. You actually know quite a lot about your experience of fear. That enables you, first of all, to be with someone else who’s afraid. But there’s something else I want to point to, which is that in addition to your fear, there’s the knowing of the fear. There’s the awareness of the fear. So that means that fear isn’t the only thing in the room. Awareness is also here. And awareness, you can choose to function from the fear or you function from the awareness. Yeah? So when I’m with people who are afraid, I help them to discover, just as you and I did for a moment, that they can be aware of their experience. And that gives them the freedom to not be trapped by it. So to bring your whole self means to bring really your whole self. Not just your emotions, just all your emotional states and your neuroses and all of this, but also your awareness. To bring this forward, too. This is part of who you are. Here’s an example. I was taking care of a dear friend of mine during the AIDS crisis in America. And he was a wonderful guy. And there were about three or four of us taking care of him. And it was my day, a Monday morning, I remember, to come and see him at his house. And when I arrived at his house, he was sitting at his kitchen table, and a strange neurological phenomenon had happened for him overnight. And he’d lost his ability to hold a fork or to stand or to speak an intelligent word. It all happened in one night.

Okänd

Yeah?

Frank Ostaseski

And it was my day to take care of him. So we went through the day doing our best and John had these anal tumors and constant diarrhea and taking care of him was a lot of work. We had to go from the bath to the toilet, back to the bath dozens of times during the day and, frankly, I got very tired. I was really tired and when I get tired I tend to lean into my role. You know, I try to be somebody to sort of give me some false strength and that’s what I was doing with John. And there he was sitting on the toilet and I was washing my hands at the basin looking in the mirror and I could see that for the first time in the day he was whispering something to me and I turned around and I heard him say, You’re trying too hard! And I was. Trying much! Too hard to be somebody, you know, to be me, Mr. Hospice, you know? And I sat down beside the toilet and I just wept. And that meeting there in the bathroom, him on the toilet, me next to him on the floor, this was one of the most intimate meetings of our whole friendship. Because you see, in this moment we weren’t so separate. Before then I was afraid. And I was afraid to acknowledge my fear. I was afraid to acknowledge my helplessness. I was afraid that if I did, we would be lost. But actually what happened was we were helpless together. And we didn’t stay stuck there. We weren’t helpless forever. But we learned, I learned something about that state of helplessness which was actually really helpful, really useful in caring for him. And so we have to be willing to enter all these different territories of our life, all the domains of our life. And when we do, again, this is what gives rise to empathy and eventually to compassion. So to know ourself fully and to be willing to bring it all forward, yeah, that’s to bring your whole self to the experience. And the same is true in meditation. I want to just add this that we’re here talking about death and caring for people who are dying. But when you sit down in a meditation cushion, you have to bring your whole self forward. Not just your transcendent self or your, you know, got it all together self. You want to bring the whole mess forward, yeah? And so you can know it and understand it and be free of your hindrances. So bring your whole self to the experience. Yeah.

Axel Wennhall

Yeah. We usually talk about meditation as a practice to be able to be present in life. And it’s quite easy to be present when you’re out in nature or when you’re cuddling with a cute dog or whatever. But the real challenge obviously comes in when life gives us those challenges as you just you explained. Absolutely.

Frank Ostaseski

You know, I have two step-s so it’s looking at those puzzle pieces and we think, oh, there’s my anger. I shouldn’t be over my anger by now. I think I’ll set that aside. Or there’s my grief. I’m so tired of my grief. I think I’ll put that aside. And when we look then, we couldn’t recognize ourselves because we’d be looking at a fragmented image of who we are. So to be whole, we have to bring it all in. We have to invite it all in, yeah? We can’t be free if we are rejecting any part of ourselves.

Axel Wennhall

And which sort of leads us further on to the fourth invitation, that to find a place of rest in the middle of things, that seems quite necessary also when things are falling apart or in the midst of that.

Frank Ostaseski

No, imagine we’ll find rest when we go on the holiday or perhaps when we go on a mindfulness retreat or something. But you know, one of the things I learned in being with people who are dying is that you’re on call 24-7, you know? And so you have to learn to rest right in the middle of what you’re doing. And meditation practice, again, can really be helpful here. You know, what meditation practice is primarily about is bringing your attention to the ever-changing moment. And by attending to constant change, the flow of that, the mind actually gets quite stable and it gets concentrated. And we experience this concentration as a kind of rest, not as a thorough brow on a really tight, you know, constipated kind of concentration. It’s a really relaxed way. Or like when you’re reading a book and you’re really involved in the book and you’re giving your whole attention to the book, it’s restful, isn’t it? So to find a place of rest in the middle of things is essential because otherwise we’re always stuck by our human drive to do more and to get more done and all this. And our nervous systems are kind of jangled and out of balance, really. I just suffered a series of strokes this summer brain strokes. And I’m fortunate in that I didn’t have any paralysis and I haven’t had any aphasia or word-finding problems. I’m able to speak fairly cogently to you anyway. But it’s confused my capacity for processing. I can’t make my iPhone work. I can’t sort things. If we say let’s go and have dinner but before we’ll stop for a coffee and afterwards we’ll have some dessert on the way home at the different restaurant, I can’t sort all those things. I know what each of them are but I can’t put them in order. And I also can’t place myself in time. It’s quite difficult for me. Time is just a kind of idea for me, mostly. So these states can create a certain degree of anxiety. So I have to learn to rest right in the middle of the anxiety. And that’s what stabilizes me. That’s what actually brings me back and enables me to function. So to find a place of rest in the middle of things. Do you want an illustration of this?

Axel Wennhall

Yes, please.

Frank Ostaseski

Okay. So at the hospice there was a woman. Her name was Adele. And she was a very rough, tough woman. A tough Russian Jewish woman. And she didn’t like Zen hospice. She didn’t like all this talk of meditation and things. So the night she was dying, they called me and I went to be with her. And I walked in her room and she was sitting on the edge of her bed with her feet sort of dangling off the edge in her nightgown. And next to her was a nurse’s aide. Very good person. And so I sat in the corner. That’s my way. Just go sit in the corner and see what’s needed before you jump in to help. And a very nice nurse’s assistant said to Adele, You don’t have to be scared. We’re right here with you. And Adele, who was this kind of tough lady, you know, she turned to her and she said, Honey, if this was happening to you, you’d be scared. Believe me. So I stayed in the corner. And a little bit later the attendant, the nurse’s aide, said, Would you like a shawl or a blanket around your shoulders? You look a little cold. And Adele shot back, Of course I’m cold. I’m almost dead. And I thought, My, I wish. I hope I have half of her tenacity when I’m dying. You know? But I saw two things in that. One of the things from sitting on the couch. I saw that she didn’t want any nonsense. She didn’t want to talk about tunnels of light or mordos or after-death experiences. She wanted authentic relationship. She didn’t want not. She didn’t want reassurance. So I pulled my chair up very close to her and I looked her in the eye and we knew each other quite well so I could be honest with her. And I said, Adele, would you like to struggle a little bit less? And she said, Yes! And I said, Okay. I noticed something. I said, There at the very end of your exhale, before the next inhale, there’s a little gap, you know, before you take the next breath. I said, I wonder what it’d be like if you could put your attention in that gap for just a few moments. I’ll do it with you. Now remember, this is a woman who doesn’t care anything about meditation. She doesn’t believe in any of the ideas of Buddhism or any of these things. But she’s highly motivated in this moment to be free of suffering. And that’s what gets most of us to sit on our meditation cushions. So there we were, breathing together. She would breathe in, I would breathe in. She would breathe out, I would breathe out. I didn’t guide her very much, but I could see that she could find that gap. And when she did, I noticed her face change. I noticed the fear and anxiety which had characterized her face relax and her face became softer. And then after a while she said, Frank, I’m gonna lie back down on the pillow here and rest now. And I said, that’s a really great idea. And she did. And not long after, you know, five or ten minutes later, she died very peacefully. I think Adele found a place of rest in the middle of things. You see, she was still dying. She was still breathing with great difficulty. None of the conditions had changed, but she found a place of resting right in the middle of them. We’re always busy trying to manage the conditions so that we can rest. When I get my list checked off, when my email box is empty, when I go on a holiday, then I’ll rest. Adele found it right in the middle of the most devastating of circumstances. So that’s what I mean about finding a place of rest in the middle of things. It’s always there for us. It’s as simple as turning our attention toward it.

Axel Wennhall

Yeah, that’s beautiful. And also a good reminder that just as you said, with to not to be defined with a fear, for example, as an emotion, that you can sort of step back into that awareness and witnessing it instead. And I mean that is what you do in meditation a lot in that kind of practice.

Frank Ostaseski

Absolutely, absolutely. All of these, you’ll see that each of these five invitations, first of all, they all interpenetrate. They all serve each other, right? But also they’re all based in mindfulness practice. They’re all based in our direct experience in meditation. And so they have a relevance for all of us, I think, in our lives. Yeah.

Axel Wennhall

I know you had your own personal close encounter with that.

Frank Ostaseski

I’ve had a few now.

Axel Wennhall

Would you mind telling us a little bit about, was it, you got a heart attack?

Frank Ostaseski

Yes, I had a heart attack. Actually, I had two heart attacks. A few, several years now, a couple of years back. I was actually teaching a meditation retreat on compassion for doctors and nurses. And I felt this pain, you know, like a lot of people have heart attacks, I denied it completely. And then I was leading a guided meditation on sensing the body. And this pain was rippling through my body. And I kept, you know, I’m a very good Buddhist, you know, so I said, oh, sensing, sensing, tingling, tingling, you know. And when I got up from the meditation, my assistant said, you don’t look good, you know. And they took me to the hospital and I had a heart attack in the middle of the emergency room, actually. And then I had to have triple bypass surgery, which is a rather big encounter, yeah. But it was a learning experience for me. I’m a pain medication. And into the room came a respiratory therapist. And he announced himself by saying, let’s take out that tube and see if you can breathe. And it terrified me, you know. So I waved my arms to say no. And there were two people with me at that moment. My son, who’s a grown adult, and my best friend, who’s a meditation teacher. And my friend said to me, Frank, feel your breath. Now, I couldn’t feel my breath. There was a machine breathing for me. My own breathing rhythm wasn’t happening. So I shook my head, no. And then he said, well, then sense your body. And I went to sense my body, but it was still full of anesthesia, and it was quite difficult to sense my body. Couldn’t feel my feet. And then I did something very simple. I pulled my friend very close to me, and I put my ear next to his mouth. And when I did this, my son, grown adult, slipped his hand under the covers, under the bed sheets, and put his hand on my chest, on my heart. And what I did was, I borrowed the breathing of my friend. I borrowed the rhythm of his breath, because until I could stabilize, actually. And my son’s hand on my chest, on my heart, was like a conduit to God. It brought forward in me a great sense of warmth and love. And so with this love, and this able to stabilize through the breathing rhythm, I could be okay. And then I signaled to the respiratory therapist to take out the breathing tube. Now I could manage it, yeah. So there’s a good question for us meditators. What will you meditate on when there’s no breath? What will you meditate on when you can’t sense your body? So we have to be careful, I think, in our discussions of meditation and mindfulness, to not get too fixated on technique. And to really think of meditation practice as a way of really being very attentive to life, and seeing what in it can really serve us, and how we can serve that life, of course.

Axel Wennhall

How did it affect that experience, your life after the surgery and when you were recovering?

Frank Ostaseski

Well, I think the thing that has been most notable in that experience, and in my recent stroke that I just had, I had a series of strokes just a few months ago. And so I’m in the midst of healing from those. The quality which has been most evident and most useful is vulnerability. You know, when we think of vulnerability, we normally associate it with the susceptibility to harm. We can be harmed, emotionally or physically. And so this engenders a tendency to create defenses, to build some kind of armor, and armoring around our hearts. And I think oftentimes, in fact, we confuse those defenses with vulnerability. We don’t actually feel the vulnerability, we feel all the defenses against it. And we know that they’re not somehow strong enough. Vulnerability is actually a kind of openness, a kind of transparency. It’s a kind of porousness or permeability. Do you remember from your high school biology classes studying osmosis? And osmosis is that process in the body where molecules move across a semi-permeable membrane. And they do it effortlessly. It happens all the time in our bodies. Vulnerability is like that. It allows the world, its beauty and its horror, to impress itself on our hearts, on our souls, on our nature. So the thing I’ve learned most from my heart attacks and from the stroke is the value of vulnerability. And I think it’s one of the most beautiful human qualities I know. Because it enables us to sense and feel and know directly our experience. And to that matter, to know directly the experience of others. So it takes courage to be vulnerable. We think of it as weakness, but actually it’s the most courageous thing. To allow ourselves to be vulnerable. To know that some of us will make love while other people make war. To know that there are children like my granddaughter who tonight will make tents out of bed sheets and couch pillows in our central room. And to know that there are other babies who are crying themselves to sleep in Syrian refugee camps. You know, it’s to recognize that we feel separate from each other, often times. And then we find our belonging with one another the moment we begin to include love. Vulnerability allows us to experience all of that, the whole range of things. And if we cut ourselves off to some part of our experience, for example, some form of our suffering, our grief, or our fear, then we can’t be vulnerable to our capacity to love, and be compassionate, and to belong. So the thing I’ve learned most from coming close to death is the value of vulnerability. And now it’s my guide. It’s the door that I walk through when I most want to know my deepest nature.

Axel Wennhall

Like you said before, it also feels in one sense connected to the last and the fifth imitation, that is, Cultivate don’t-know-mind, which sounds like a paradox. What do you mean with Cultivate don’t-know-mind?

Frank Ostaseski

It is a paradox. And you know, like in Zen we use the practice of koans. Koans are slogans like this that challenge our linear thinking and our logistical, you know, logical minds. To cultivate don’t-know-mind is not an encouragement to be ignorant. It’s to not be so full of our knowing. You know, when I walk into a room where someone is dying and if I’m full of my knowing and my expertise, I’ll miss half of what’s going on there. So I have to open myself to what I don’t know. And it’s not just not knowing facts. It’s a quality of mind. It’s a mind that’s characterized by curiosity, by a sense of wonder. Suzuki Roshi, the famous Zen teacher, called it beginner’s mind. He said, In the expert’s mind, there are few possibilities. In the beginner’s mind, there are endless possibilities. So a don’t-know-mind isn’t stupidity. It is curious. It is receptive. It’s full of wonder. Now imagine if when someone is dying, imagine you’re dying, and you’re in your deathbed, and people come in the room with all kinds of advice for you, and all kinds of ideas about how you should go through this. And I once read, you know, they tell you. I mean, can’t you see how exhausting that would be? And how you would feel so isolated and alone in the bed. Whereas if somebody came in, weren’t so full of their knowing, and were able to sit with you, and explore with you, and learn from you about what your experience is, ah, so much more would be possible. So meditation practice is a great place to practice don’t-know-mind. It’s a process of continuous discovery. And that’s, for me, an exciting way to live. Yeah.

Axel Wennhall

I think when I even think about the sentence, I don’t know, I feel vulnerable. Yes.

Frank Ostaseski

I think exactly that. It makes you vulnerable. And that doesn’t mean that you’re going to be hurt. It means that you’re open to being impressed upon. The world can impress itself on you. The beauty of it. I mean, when you go into the woods, into nature, as you were saying earlier, isn’t that what happens? We relax in some way, and the wind blows right through us, and the smells of the forest, you know, permeate our very being. Yeah. We’re vulnerable to the beauty that we find there. Right. And we can be vulnerable to the difficulties of life, too. You know, for example, I was teaching a retreat just a few months ago, before my strokes. And a woman said to me, I don’t read the newspapers anymore. They’re too terrifying. They’re just full of bad news. And I said to her, No, I think it is just people who are alone, in their beds, in pain, isolated. And my heart opens. And my heart opens not only to those individuals, but to myself. And then I have the compassionate capacity to continue to stay with what’s difficult for me. So compassion isn’t just about the other person. It’s about ourselves as well. You know, one thing I want to add to this is that we normally think of compassion, it’s thrown around a lot in, you know, spiritual circles these days. And mostly it’s thought of as the capacity to remove suffering, or the wish to remove suffering at least. And that’s true. And that’s a beautiful thing about it. But there’s another quality to compassion, which is that it allows us to tolerate, to stay with what seems impossible. And to hold ourselves present for what’s difficult, the suffering of our life. And by doing that, the defenses against that suffering fall down. They just collapse. And then we can see the true causes of the suffering. And then we can intervene skillfully. Make an intervention that helps. So one of the other facets of compassion is that it helps us to discover what’s true. And it particularly helps us in the territory of suffering. It helps us to discover what’s true, what are the true causes of the suffering, so that we can skillfully act to reduce or remove those causes. So for me, compassion is very practical.

Okänd

Yeah. Yeah.

Frank Ostaseski

So to really cultivate don’t know mind. We so love our knowing. And we’re so proud of our knowing. And we get so, we define ourselves by it, don’t we?

Axel Wennhall

Yeah.

Frank Ostaseski

And I think it’s good to let it relax a little bit sometimes. You know, I was with, I was in Japan last year. And I was with an artist who makes, you know, those wonderful scrolls that they have in Japan, and on which is a piece of art or a calligraphy that is glued in a way to these scrolls. He makes the scrolls. And he’s quite an artisan. And I said to him, you’re a beautiful artist. He said, no, I’m not an artist. I’m craftsman. And I said, how do you mean? He said, it’s like underneath this floor, there are beams that support the floor. We don’t see the beams, but they’re there to support the floor. He said, my scroll is like that to the artist. He said, my job is to support the artist, actually. And by, by fading into the background as much as possible, so that the art can really be seen for all its beauty. That was really lovely to hear him say that. And I think sometimes, when we relax our knowing, we’re a little bit more like that, you know. And so, something beautiful or true can show itself in our life. Yeah, sure.

Axel Wennhall

What comes up to my mind is the ability to hold a space or to give space to other people.

Frank Ostaseski

Yeah. Yeah, and isn’t that what we do in meditation? In a sense, aren’t we holding space for ourselves? And then, whatever needs to occur can occur. I mean, there’s a wonderful English pediatrician. His name was Donald Winacott, and he coined the term the holding environment. And what this would refer to is young children, toddlers, when they’re learning to walk, for example, they stand up, you know, they toddle along very unbalanced and fall down, and oftentimes they scrape their knee or they feel shocked or startled. And the mother or the father or some adult comes along and picks them up and holds them. And when they hold them, what they do is they lend that child their nervous system, actually, and it helps the child to regulate. And then, when they put the child back down, inevitably, what happens is the child can go further now. The child can go further than they first imagined, in a way. You know, stumble along a little bit further. I think we could think of meditation like that, that our awareness is a kind of holding environment. And when we feel that holding, we can go beyond our limiting stories of ourselves. We can experience the fullness of our nature. We can know much more intimately all that we are. But in order to do that, we have to feel the loving holding of the awareness. Awareness itself, it’s like, well, it’s like this holding. It doesn’t reject anything. And love infuses awareness sometimes. And I’m not talking here about mushy, sentimental love. I’m talking about the strength of love. You know, love is strong because it doesn’t reject anything. You know, in America- I don’t know how it is there, but we have these very entitled communities that are gated and you have to have a special passcode to get through the gate, you know, into a wealthy community. Sometimes love is not a gated community. Everything is welcomed, even those parts of yourself that seem unlovable. It’s all welcomed.

Axel Wennhall

You’ve been sitting with a lot of people who were about dying. What was the question that mattered most to them?

Frank Ostaseski

Well, of course, there’s no one set of question, different things for different people. But what I saw very often actually was, well, it relates to what we’ve just been talking about. People mostly wanted to know, not what happens after I die. They want to know, am I loved? Am I loved? And did I love well? Now, those are the two most important questions that people ask at the time of their dying. Aren’t they important to us now? Shouldn’t we live into them now? Shouldn’t we discover as much as possible about those questions now?

Axel Wennhall

Have you found it in your spiritual practice that those questions came to the conclusion as well?

Frank Ostaseski

I think they’re central in my inquiry. I try not to draw too many conclusions about it, but I try to bear witness to how I love and how I am loved. I mean, an example is that recently during these strokes, my dear bride, my wife, has been unbelievably available to me and helping me daily with my inability to do day-to-day functions. The community of people that I trained at Zen Hospice and through the Meta Institute, they showed up for me. They came and sat with me all night in the hospital. And I think in part because I lived a life of integrity and I lived a life in which I tried to put love first. And it’s not that it comes back to me like a debt. It’s more like this is what it engenders. When we live a life of integrity and love, it engenders a sense of belonging, a deep sense of community. So yes, they are two really important questions for my life and I share them with you in the hopes that they will be that for you too.

Axel Wennhall

Yeah, no, but it’s been my discovery so far yet that it’s all about love. But yeah, when I can experience life as fully as possible, it’s very clear and vivid. Sometimes it gets a tangle, it gets abstracted, but those experiences, those glimpses, it’s very clear.

Frank Ostaseski

Yeah, and I’m not sentimental about any of this aid to us during the time we’re dying, but I don’t do it just to prepare for my dying. I use dying to show me how to live my life well. You know, I mean suppose there’s endless lifetimes after this life. Well then how would you want to live this life? Yeah, probably with some integrity, some, you know, capacity to love those you care for. And suppose there was no life after this. This is it. Suppose it just ended when you took your last breath. Well then how would you want to live this life? Well, you would want to live it with a lot of integrity, right? With a lot of love for the people that you care about. So we can use the presence of death in our life to show us how to live this life in a way that has meaning and That’s what dying people have taught me over the years.

Axel Wennhall

Thank you. Thank you, Frank. Before we are going to end our conversation with a guided meditation by you, we just have just a few quick last questions. If you could make a time travel and go back and give an advice to yourself when you were about to start meditation, what would you say to yourself?

Frank Ostaseski

I mean, relax. I mean, it’s true that, you know, I got a bad back now. And I think it’s partly because I was striving so much as a meditator, you know, enduring. I was very good at enduring in meditation. You know, I said, I don’t know if we’ve shared this, but mostly we think of that balance of effort as applying more or less energy in meditation practice. I think of it as a balance between relaxation and interest. The body’s relaxed, the hearts relaxed, minds relaxed. Mindfulness emerges much more easily. And when the mind is really engaged, it’s curious and it’s interested, then there’s a kind of brightness, isn’t there? The kind of bright mind. And it not only opens the mind, but it lifts up the body and inspires the heart. So I think that’s the right balance for us to find between relaxation and interest.

Axel Wennhall

I’ll take that advice as well. I see a lot of striving in myself, so that’s great. And we have a segment in the podcast that’s called five quick questions.

Frank Ostaseski

Okay, I have to get five quick answers then.

Axel Wennhall

Exactly. Okay, perhaps it will be lost in translation here, but I’ll give my best. What makes you present?

Frank Ostaseski

My granddaughter.

Axel Wennhall

If you had to recommend one book about meditation, which book would it be?

Frank Ostaseski

Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind by Suzuki Roshi.

Axel Wennhall

What are you grateful for right now?

Frank Ostaseski

Breathing.

Axel Wennhall

When was the last time you cried?

Frank Ostaseski

This morning. I think that crying shakes loose the calcification around our hearts.

Axel Wennhall

What’s the best advice you got?

Frank Ostaseski

When I was a young man and I went traveling across the country, my father said, you’ll come to a place that’s very beautiful. Stop, savor it, but don’t stay there for too long. There’s another beautiful one just down the road.

Axel Wennhall

Perfect. Thank you. I am again, we’re grateful for you taking this time and for also guiding us into this meditation. So I will just give you the floor.

Frank Ostaseski

All right, let’s see. I think of meditation practice as a way of becoming intimate with ourself and the world around us. So let me guide a practice that might help us. So let’s begin by pausing. Just pause. Pause is an opportunity to step back from the momentum of our life. It’s an opportunity to remember who and where we are. It’s a way of releasing ourselves temporarily from habit. So let’s just pause.

Okänd

Now relax.

Frank Ostaseski

Allow the body to relax, the heart to relax, consciousness to relax. to recognize that mindfulness emerges much more easily in a relaxed body, heart, and mind. It’s not the goal of the practice, but it’s conducive to the practice. So pause and relax. Pause and relax. And now open. Opening all the senses. Allowing the mind to be open, the heart to be open. One of the characteristics of an open mind is a quality of spaciousness, infused with curiosity or an interest to know. Open. Pause. Relax. Open. And now allow. Allowing takes us beyond accepting and rejecting altogether, beyond fear and hope. We allow our whole experience to show itself, to display itself on the screen of our awareness. Allowing is a kind of trust. Trust in allowing. Pause.

Axel Wennhall

Relax.

Frank Ostaseski

Open. Allow. And now become intimate. Intimacy is a way that we know something from the inside out. No separation between subject and object. The breath arises and it’s known immediately. A thought comes into the field of consciousness and it’s recognized. At the very same time as it arises. To become intimate is to not have any walls against any part of our experience. To become intimate is to know through immediacy. Pause. Relax. Open.

Okänd

Allow.

Frank Ostaseski

Become intimate. Thank you very much.

Axel Wennhall

Hmm thank you. Two last questions before we say goodbye for now. But first, do you have any suggestions on other guests that you would be keen to listen to?

Frank Ostaseski

Yes, one that might fit well with you is a fellow by the name of Mark Coleman. And Mark is a meditation teacher at Spirit Rock, trained by Jack Kornfield. But he also has a mindfulness training institute, which he teaches in both in Europe and here in the States, teaching people how to become mindfulness facilitators. But his specialty is mindfulness in nature. And so he’s really wonderful about helping people to recognize how to be mindful in nature and how that can support our practice. So he’s a wonderful guy and I’m happy to introduce you to him. I don’t know what his availability is, but he’s a dear friend and I’ll suggest it to you. And given where you live and your the clientele of people who listen, I think it would be a good match for you.

Axel Wennhall

Sounds awesome, thank you. So thank you so much for taking the time. I’m glad that the power got back on as well.

Frank Ostaseski

Yes, I’m so sorry about that. I have nothing I could do about it, but I appreciate it. I’m glad we got back on. It was just a freak random thing that went out.

Axel Wennhall

Thank you so much.

Frank Ostaseski

You’re welcome. Thanks again. Have a great day. Bye-bye.

Axel Wennhall

Bye. Thank you for listening to this episode of the Swedish podcast, Meditera Mera. We hope you have been inspired by our conversation and by Frank’s meditations. This podcast is done by me, Axel Wennhall, and Gustav Nord. And together we run Breathe In, where we arrange meditation and adventure retreats. With the help of meditation, nature, and adventure, our aim is to discover the present moment, both on our trips, but also when we get back home. And we currently have three upcoming retreats. A weekend retreat just outside Stockholm, where we’re going to hike and meditate. And then we have another retreat in Sweden, firstly to a Sunday, where we’re going to explore plant-based food and mindful eating, together with hiking and meditation. And then we’re going back to the Italian Alps for hiking, mountain climbing, and downhill cycling. And a lot of meditation, of course. If this resonates with you, you’ll find more information on our website, breathein.se. As mentioned in the beginning of the episode, this was our third international guest. And hopefully we have a few others coming up. And we also hope this is only the beginning. Because we believe that meditation and mental health will be our next health revolution. And in order for that to happen, we see that meditation needs to be explained in an easy, understandable, and also a scientific way. And that’s exactly what we hope to achieve with our guests. If you have any suggestions on inspiring guests, please email us at hi at breathein.se. And if you like this episode, please share it to your friends, so we can inspire even more people to discover the present moment in meditation. And if there’s something that we will bring with us from the conversation with Frank, it’s that don’t wait to love.